After working for some years in Tanzania, Burundi and the Democratic Republic of Congo, in the field of cooperation, many people asked me to tell and then write about my experience.

For a long time I hesitated, because I did not want to talk about the specific organisations I worked with, and my conclusions, derived from first-hand experience, informal chats with colleagues, and from studies and books, encompass a much broader horizon than I was able to touch upon. This horizon, however broad it may be, is nevertheless limited. I was afraid of offering easily generalisable conclusions, thus contributing to a simplified, flat and potentially damaging worldview. Instead, my aim is to explain something about this sector and its difficulties, for those who are not familiar with it, and to open a debate for those who are.

I will therefore make a presentation, from the perspectives of some of the people and entities involved.

Humanitarian worker – international staff (expats)

Humanitarian workers (expats) are people who, for one reason or another, have ended up working in the humanitarian sector, mainly for NGOs (such as Oxfam, Intersos, Doctors without Borders..) or for United Nations agencies (UNICEF, World Food Program, UNHCR,..). The roles they occupy are mainly coordination roles: manager of operations, finances, logistics, expert in a specific sector (such as Health, Education, Gender Issues,..), as you can see on ReliefWeb, the main job search portal in the sector. Very few organisations have international staff working directly with people. One of these is Doctors Without Borders, where doctors, nurses, social workers, community trainers, live in small bases in conflict/natural disaster zones, in direct contact with the local people.

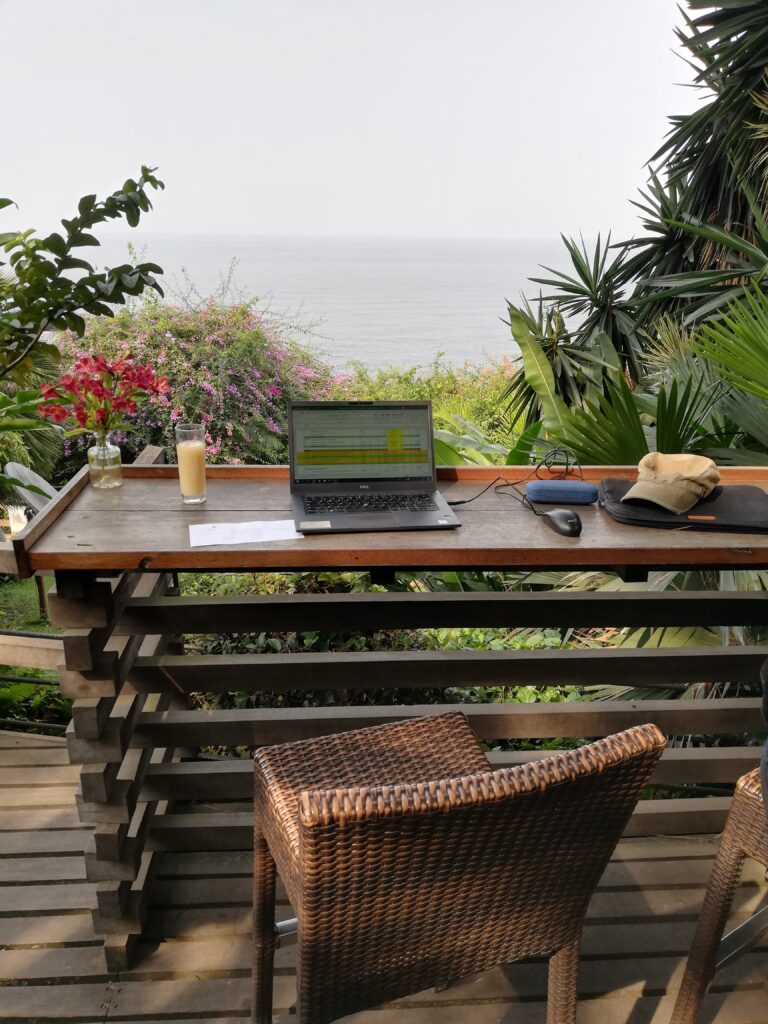

The others are based in large provincial cities (as I was in Goma, in the east of Congo), capitals or regional centres (such as Nairobi for East Africa, and Dakar for West Africa). These workers do visit the populations they work for, but they do not live with them. They live in the organisations’ bases, closed off with walls and guards from the outside world. During the day they work with local and international staff and in the evenings they go out to bars and restaurants (e.g. le Chalet in Goma) where they pay in dollars, which are expensive, and where they meet up with expats working with other organisations. This bubble of aid workers is referred to by former humanitarian and scholar Severine Autassere as Peaceland (in her very interesting book of the same name).

In contrast to Development, which operates in poor but peaceful areas (such as Senegal and Tanzania for example), Humanitarian Assistance operates in areas of war, civil war, armed groups, natural disasters or epidemics (such as Ebola). The objective is theoretically to save lives and restore the normality of life before Development comes into play. The projects have a limited duration and usually last a maximum of one year. However, crises last much longer. For example, in eastern Congo, there has been violence and armed groups for almost 30 years (since 1994, genocide in Rwanda), and millions of dollars and goods in humanitarian assistance flow in every year.

This makes humanitarian organisations stay in place for a very long time, but they have to manage to finance themselves with various limited duration funds provided by public or international bodies, each of which has its own area of activity and specific objectives. For example: UNICEF funds projects for children, UNHCR for refugees, UN-Women[1] for women, as well as the big international funders: USAID (U.S. Agency for International Development) and DG ECHO (European Commission’s Directorate-General for Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid), have their own geographical and thematic priorities.

The NGOs working in the field struggle to give continuity to their activities by continuously securing new funding. This funding is indeed necessary for the very existence of the NGOs. The salaries of expats, local staff, cars, fuel, base rent, etc. are all covered by a percentage of the projects that normally cannot exceed about 20% of a funding: the so-called indirect costs of the organisation. The rest has to be spent on goods and services provided directly to the recipients of the intervention (so-called ‘beneficiaries’ in humanitarian jargon).

One of the efforts of organisations is to continuously write new projects in response to various public calls for proposals. Sometimes these calls for proposals have a very short deadline, even as little as one week, and this is one of the reasons why the work is particularly stressful, because in these cases you have to work through the night until the last available hour. Then you have to do the activities, write the various intermediate and final reports, collect all the indicators to show that the activities were well done in terms of expected numbers and quality, coordinate the local staff, take care of the visibility on social media and above all manage endless problems that can arise in contexts where the state is very weak: corruption, fraud, security problems, an armed attack on one of your teams,…

Not all NGOs depend on public funders. MSF for example, which is one of the largest organisations in the world, depends to a large extent on funding from private individuals and does not have to waste so much energy in looking for funds and is also free to do what it wants (not having large donors with their own conditions).

Humanitarian aid is in general an extremely stressful job. Why does one do it?

For different reasons. I believe that those who start out are mainly motivated by the desire to do good, to help others and at the same time by the curiosity to travel the world and the desire for adventure.

When you begin, however, you are confronted with an endless series of problems, such as those mentioned earlier, and you realise that a good part of the work consists of doing what your donors and your organisation ask you to do, and that this takes priority over the needs of the local population. For example, to write a good project, you would have to take the time to do field studies, to meet for months with the various local population groups, to understand the context, etc. When a donor comes along and opens a call for just one week, if we are talking about quality, one should often refuse to write it.

But how do you explain this to your organisation, which needs funds to survive? So you write projects in a short space of time, you accept, at the donor’s request, to work in new areas where you have no experience and where you are not known by the local community, you do bigger interventions than you could manage, you favour quantity over quality. You come up with projects with thousands of beneficiaries so that your donors can explain to their government, the public or whoever: ‘Voilà in this region we have helped 50,000 displaced persons, here 130,000,…’. In fact, it would be much more complicated for them to explain that so much money has been used to help a few people, but that for those people life has really changed for the better.

The result is often poorly conceived projects that risk doing more damage than anything else, just like any kind of poorly planned intervention in any other sector. Only here, the funding is often very large. We are talking hundreds of thousands, sometimes millions of dollars. And they are written by people who have come from another part of the world and have little understanding of the context and the problems.

To give you an idea, it is as if there was a natural catastrophe in Rome, the state was not capable of managing it, and then several NGOs arrived from a different part of the world and for example a Congolese organisation managed a few hospitals, another of Amazonian natives took care of others (according to their studied methods of natural medicine) and another of Australian aborigines arrived in support of a few schools with their pedagogical methods. All this with projects lasting six months/one year that are sometimes extended and sometimes not. We agree that it would be chaos.

To come back to us, our aid worker tries to do his best, but is quite discouraged by the results. However, in this sector there are organisations that are known to work better than others, so his hope is to move to one of these (more serious and professional) organisations as soon as possible, so that he can feel more useful to people and also receive better and more stable conditions (salaries, holidays, bonuses,..).

Working conditions are another reason why people work and continue to work in humanitarian aid. If we exclude first work experience, often internships, the lowest salaries are at the MSF (Médecins Sans Frontières) level, which offers around 1700 euros/month. Larger organisations offer around 2500/month for lower positions up to 7000 for higher positions, not to mention the United Nations, which offers some of the highest salaries on the market. Added to the salary are generally holiday days, R&R (Rest and recuperation) in which every 3 months or so you are paid to leave the country to go and relax somewhere quiet like Zanzibar for a week, and international health insurance.

This may come as a surprise to many who believed that those who work in the humanitarian sector do so only out of passion and with little money. In fact, I believe that a good part of the NGOs started out as volunteers, unpaid, who went to crisis situations and helped as they saw fit. Over time, however, it became apparent that the lack of professionalism and control led to huge mistakes (paid for, as always, by the local communities) and so the sector gradually became more professionalised and now requires specific studies and previous experience. In return, of course, it must offer attractive salaries and conditions.

In addition to the desire to do good, to travel and adventure, to wages and working conditions, there is also the ability to make an impact on reality (and power).

If we come from a country like Italy, where at the age of 30 one is still considered to be a kid, where one is stuck in rigid hierarchies and where to do anything, such as putting up a wall on one side, one needs endless permits, it will not seem true to find yourself in a situation where at 30 years old you are in positions of responsibility, where you are considered, and where, if you have an idea, you can realise it and see it realised within a few months. This feeling of responsibility, this power to act in reality, I think is one of the strong and attractive points of the job. Added to this is also a question of skin. Even if you don’t want to, living as a white or foreigner in a country of blacks and where there is poverty, you get used to being treated with an attention and deference that is unthinkable in our country and this feeling of interpersonal power, in the long run, is likely to be addictive.

Humanitarian worker – local staff

In order to respond to this whole range of problems, humanitarian assistance continually makes great efforts and campaigns to improve itself. One of these is the localisation of humanitarian assistance, which in a nutshell implies that local people are increasingly the real actors of the response. This is also why most NGO staff are now local staff. They are the ones who are there for years, who know the organisation in depth and who work in direct contact with the beneficiaries.

Why do they do this? On the one hand because a lot of companies in which they used to work closed, so former building/public works engineers / architects reconverted themselves in humanitarian roles such as WASH (water, sanitation, hygiene) coordinators or School rehabilitation engineers. Because they want to help their community but also because it is a well-paid job (although much less than international staff, already $1,000/month is still a very good salary) in an unstructured context like the humanitarian one, where there is a general lack of work.

It is local staff who are personally involved in the management of huge projects such as the distribution of millions of dollars to the families of displaced and vulnerable people; it’s them who visit house after house, family after family, and fill in the vulnerability criteria, allowing one family or another to enter the assistance programmes. Needless to say, this enormous power leaves room for scams such as the one involving the American organisation Mercy Corps in 2018 in DRC, from which an estimated fraud of more than $600,000 was reported, and that in the previous two years some $6 million may have been ‘lost’ by various organisations.

Local people, the ‘beneficiaries’ of assistance

If you take a Land Cruiser and drive up the muddy roads of North Kivu, if you drive through the green hills that give Masisi Territory the nickname ‘Little Switzerland’, you will also find the villages of mud houses, and finally them, the local communities, the IDP camps, their stories of life and suffering. All this, and above all their poverty, do not seem to have been touched in the slightest by some 30 years of international support. The only clue are the many banner signs along the road indicating the projects that have taken place, the donor and logos of the organisations involved, a few schools and water wells. The purpose of humanitarian assistance is mainly to keep people alive, not to leave a long-term trace, but is it possible that the great floods of funding for more than 30 years have left so few marks?

Local authorities

One of the things that struck me most was the lack of cooperation and support from the local authorities towards humanitarian organisations. At first, I naively thought that aid workers were seen as someone who was there to do good and to help the population, and that therefore they would have received a certain support from the authorities. I would have been surprised to discover that local authorities, from the simplest policeman on the street, to regional ministries and beyond, use every trick in their power to gain money and tax organisations, even at the risk of shutting them down.

To give an example, when I applied for a visa, my passport got lost for months in the central office for not wanting to ‘facilitate’ the process.

The power that local authorities have over humanitarian organizations is very high, because they are the ones who authorize them to work in the country and in the various areas of intervention. To give an idea, a medical NGO that wants to support a local hospital in the region X must have authorization from the Ministry of Health, in addition to having visas for its expat staff from the Ministry of Immigration, and authorizations from other ministries. Without those permissions, they simply cannot be there and work.

The Democratic Republic of Congo might be a special case as it has some of the highest levels of corruption in the world, probably due to the Mobutu era (dictator from 1965 to 1996) when civil servants were asked to make do as salaries did not arrive or were insufficient (article 15).

It must also be said that in many humanitarian crises where the social tissue is disintegrated, it’s possible that officer X may not give a fig about his Congolese brother in need of help.

However, this indifference on the part of the local authorities could also suggest that humanitarians are not seen as generous and ‘altruistic’ people, but as someone who serves their own interests, with high salaries, and who takes advantage of the poverty of local people. And this could morally authorise them to line their pockets, without making too many scruples, “if they do it, why not me?”.

Armed groups

The history of violence and suffering in eastern Congo dates back to even before Belgian colonisation, to when the area was controlled by Arab merchants like Tippo Tip, who traded ivory and slaves and who among other things introduced Swahili into the region. A very well-done book called Congo, by David Van Reybrouck, explains how this led to the current situation of more than 100 armed groups in eastern Congo. Large groups, small groups of two and three people, which spring up, merge, control a hill, a road or an entire territory, with high-sounding names such as ‘Alliance des Patriotes pour la restauration de la démocratie au Congo’.

Joining an armed group is often one of the few opportunities local youth have. They are the ‘bad guys’, the great cause of suffering in this region of the world. Partly financed by neighboring countries, by international interests, partly supported by the control of mines, by the taxes they impose on small local traders, these groups instead let most humanitarian organizations pass through undisturbed. Why?

We can believe that armed groups are not, a priori, against access to health, food and so on for their population. Their aims is often to gain territory, control an area ect. but not always to have their population starving. Someone or their children and families might use services such as medical services themselves, and many of the NGOs gain access to territory through negotiators recalling the Geneva Conventions (and sometimes with the help of a few packs of cigarettes).

However, one question does arise: do these groups make money directly from humanitarian assistance? Is some of the money and goods distributed actually going into their pockets?

And if so, given that they are precisely one of the main causes of the suffering that one would like to alleviate, how do we know that we are doing more good than harm?

Humanitarian assistance should be neutral and has humanity as principle so even if, while helping the population in need, a little bit of “help” goes into the pockets of some armed group, it should be ok.

However, if armed groups earn so much money from humanitarian assistance, so much so that they commit violence and massacres precisely to maintain a ‘humanitarian’ situation and ensure the constant flow of new projects and funds, then it would no longer be OK.

In fact, the question remains unanswered, given that in these disastrous and corrupt countries like the DRC, there is no state or international agency that does not gain something from the great humanitarian machine and therefore has an interest in studying its negative effects in depth.

What can be said, however, is that already in 1994, at the beginning of the humanitarian crisis in the east of the DRC, in the Mugunga refugee camp in Goma (for a long time one of the largest in the world) the same Hutu armed groups responsible for the Tutsi genocide in Rwanda were to be found, mixed in among the refugee families, and they largely profited and reconstituted themselves thanks to humanitarian assistance. According to Linda Polman’s book “What’s Wrong with Humanitarian Aid?” some international organisations estimated that, on average, Hutu armed groups took over about 60% of the distributed goods, partly for their own use and partly to sell them back to civilians. This situation was so obvious that it led MSF France to leave the camp in December 1994 with a statement denouncing this situation. Soon afterwards, other branches of MFS took its place and the other NGOs continued to work in the Mugunga camp as if nothing had happened, financed by a huge flow of international funding.

Donors

Where does all this money come from and how much is there? In contrast to Development, in the case of humanitarian assistance the money is not lent but is in fact ‘given for free’. It is a lot of money, but much less than in development. Some of the money comes from private donations, but this is the smallest part. In fact, the money comes mainly from states and their fund distribution bodies. In 2021, the total amount of money donated (by official donors) was USD 29.3 billion, so about one sixth of the development money. The main donors of humanitarian assistance are the United States through its USAID entity, which alone finances $11.6 billion, 38% of the total. Right behind is the European Commission, Germany, Sweden, etc. (OCHA).

Why do they do this? Theoretically as a purely philanthropic matter, since the cornerstones of humanitarian assistance are precisely: humanity, neutrality, impartiality and independence. However, when it turns out that the main donor is the United States itself, the doubt may arise that this is not just altruism.

What interest can a state have in giving money in humanitarian assistance?

In fact, humanitarian assistance can be an instrument of a state’s foreign policy, a very neat instrument by the way, since it is commonly thought of as something good and generous. In a small article I had written during my master’s degree, I had analysed ECHO (European Commission Humanitarian Assistance) funding in 2016. Here, more than 50 per cent of the funding was absorbed by the Syrian crisis and neighbouring countries, probably to stem the flow of refugees to Europe who had been sent back to Turkey from the Greek islands.

In other countries such as the Democratic Republic of Congo there are enormous mineral riches and one may wonder if there are somehow links between the flow of money in humanitarian assistance and the exploitation of these mines.

In other countries, no great riches clearly emerge to explain possible dual purposes of aid.

The italian magazine Internazionale of 16 December 2022 picks up on a New York Times article of Declan Walsh on the US rapprochement with Africa. Africa is one of the continents with the largest population growth and it is estimated that by 2050 it will be home to a quarter of the planet’s inhabitants, thus constituting a huge new economic market and the reason why China and Russia are exponentially increasing their influence on the continent. According to the article:

” …the United States continue to exercise significant influence in Africa. American diplomats played a crucial role in the recent peace agreement in Ethiopia and […] Washington sends billions of dollars of aid to the poorest corners of the continent, far more than China and Russia.” (Internazionale 1491, p.29)

From which it appears that the aid sent is seen as a foreign policy tool useful for maintaining influence over countries and continents.

How this actually works, for me is still a mystery. When I did an internship at the European Commission, in one of the geographical offices dealing with humanitarian funds, I participated in the selection of funding and projects for South Sudan for the year 2017. What I could see was that not only was there no outside influence in the selection, but that everyone was really trying to choose the best projects and do their best. The choice of how many millions of euros to send in general to a single country/crisis or another, that is a political choice on which the European Parliament and member countries can have more or less informal influence.

Conclusion

In conclusion, it is clear that humanitarian assistance also inevitably has negative repercussions. The key question is: are we sure that the good that is done outweighs the harm, especially in the long term? Even in the most ‘puritanical’ organisations such as MSF, there is a debate about whether offering a quality medical service free of charge will in the long run prevent the development of local hospitals and facilities.

Many colleagues from different NGOs responded to the question by saying that ‘yes, the situation is complicated, but if one saves even one life, that alone makes sense’. However, we are talking here about large programmes financed with millions of dollars, which should have a positive effect on a large scale and overall, and cannot be justified only by ‘a few lives saved’.

It must be clear that overall, more good is being done than harm. At the moment, however, the question remains without a clear answer, since, as mentioned before, there is a lack of independent structures whose funds are not tied to those of the humanitarian sector, and whose mission is to do serious and in-depth research and to express an opinion on this.

Personally, I believe that to change the world for the better, we have to get outside the logic of profit and interests that underlie the suffering we want to alleviate. The humanitarian sector has become more and more professionalised and in doing so, willingly or unwillingly, it has become a mechanism of the system, where the human side, values, the desire to do good and altruism have increasingly taken a secondary role.

To those who ask me: “So, what to do, to whom can you donate money?” I often answer: “to small organisations or people who work in a small but quality way, who do it because they really believe in it and do it for years and years even if they don’t have a fixed salary and good conditions, to a Congolese lady who supports 15 street children in her home, to Yaneth of Lila Mujer who works every day in Cali in Colombia with HIV-positive women, to countless others you may meet or to a friend of yours who simply needs it.

This is not to say that all big organisations are to be dismissed. Millions of people currently depend on humanitarian projects around the world and, like many former colleagues, I believe that if humanitarian assistance were to be suddenly withdrawn, it would probably be a catastrophe.

Having said that, donating a portion of our money is but a limited and often rough way of affecting reality. If in order to get it we have contributed even indirectly, with our work, with our lifestyle, to feeding an economic system based on injustice and individualism that are the great causes of pain in the world, then we are clearly back to square one.

To really do ‘good’ it is necessary to see the world with open eyes and in its complexity and to go deep inside ourselves to eradicate the seeds of anger, fear and ego that everyone has within them so to avoid them germinating and replicate in the outside world what we actually want to fight.

it is necessary to learn to face a problem without looking away or acting at all costs just because looking hurts too much. The paradigm we grew up with, ‘doing is always better than not doing’, may no longer be valid, and perhaps never was.

[1] It may surprise you, but most UN agencies do not work directly ‘in the field’, but rely on international or local NGOs to do the work and have a role in selecting partners through public calls for proposals, quality control and external support. Among the UN agencies that do direct work is IOM.